In the packaging industry, a common problem is Product Giveaway – also known as Net Content Control or The Overpack (or Overfill) Problem. I like to call it “The Packer’s Dilemma” because of two competing needs inherent to the business: on one hand, ensure that product net weights meet the stated label weight; on the other hand, minimize the amount to which you fill over that label weight (and thus give away product).

In the packaging industry, a common problem is Product Giveaway – also known as Net Content Control or The Overpack (or Overfill) Problem. I like to call it “The Packer’s Dilemma” because of two competing needs inherent to the business: on one hand, ensure that product net weights meet the stated label weight; on the other hand, minimize the amount to which you fill over that label weight (and thus give away product).

I first ran into this early in my career when I was working with a company that packaged a popular brand of window cleaner. This client set up a system to collect data in a filling operation across a multi-head filling machine.

Here’s how my client described the results of his effort:

“We were able to reduce the variation in the amount of product put into bottles across a 16-head machine. By bringing all the heads in alignment, we reduced average overpack by two grams. Two grams of our product means absolutely nothing to the consumer. But because of the volumes we run through here, we saved an enormous amount of money, and it all fell directly to the bottom line.”

Product giveaway isn’t just a packaging problem

Since then, I’ve seen this same problem many times, in many product segments. From packaging pretzels to potato chips, from ketchup to cookies, from bacon to lubricating oil, reducing material costs is a big deal. And this isn’t just a packaging problem. It applies in other industries too, as I describe below.

“From packaging pretzels to potato chips, from ketchup to cookies, from bacon to lubricating oil, reducing material costs is a big deal.” Packaging companies, however, have a strong incentive to meet the minimum label claims on their products. High profile litigation from individuals and consumer watchdog groups can cause significant damage to a brand.

Memories linger… the bad taste of underfill

Social media makes the problem worse.

One example of this is a lawsuit against Heinz ketchup that was settled in 2000 after five years of litigation. The suit alleged that Heinz had underfilled product packages. Twenty years after the initial complaint, and 15 years after the suit was settled, the incident is still remembered and shared in social media.1

Given that incentive, it is no wonder that many packaging companies intentionally overfill their packages. But remember my window cleaner friend:

“Two grams of our product means absolutely nothing to the consumer. But because of the volumes we run through here, we saved an enormous amount of money, and it all fell directly to the bottom line.”

NIST Handbook 133

The US Department of Commerce, through the National Institute of Standards and Technology, publishes the definitive guide for testing net contents of packaged goods sold in the United States: Handbook 133, “Checking the Net Contents of Packaged Goods”. The Handbook is available online.2

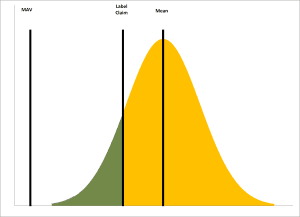

The Handbook recognizes that some variation in filling processes is inevitable, and provides guidelines for acceptable variation. These guidelines take the form of two requirements for compliance:

- In an inspection lot, the average of all of the packages must be at least equal to the Label Claim on the package.

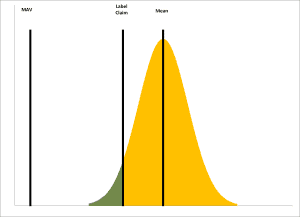

As long as the Mean is above the Label Claim, anything above the Label Claim is overpack and constitutes profits that are given away. - Some individual packages may be filled below Label Claim, but no individual package may be underfilled by more than the Maximum Allowable Variation (MAV).

Why Check Weigh Systems are Insufficient

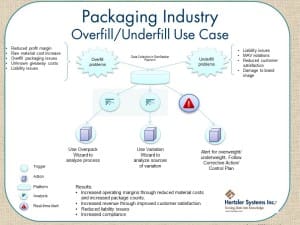

Many packers have built their Net Contents management effort around sophisticated, in-process check weigh systems. Although these systems ensure compliance, they only identify individual units that weigh less (or more) than some preset specification.

These systems do nothing to look at trends or provide knowledge to continuous improvement teams that can lead to optimized fill weights, which can leave significant amounts of money in overfilled packages. As our window cleaner packager pointed out, this value means a great deal to the packer, and no consumer good will is lost by ensuring tighter compliance to the Label Claim.

The Three-step Process to Reduce Overpack

The remedy for the Packer’s Dilemma is deceptively simple:

- Get the filling process in statistical control.

- Systematically reduce variation in your filling process.

- With the process stable and predictable, and with reduced variation in your process, you can now adjust your process to run closer to the Label Claim – thus reducing the amount of overpack.

Step 1 – Make better use of real-time, actionable intelligence to bring the process into statistical control

The good news is that by making better use of real-time, actionable information, packers can have it both ways. They can ensure compliance to Label Claim and at the same time optimize their material resources. Here is how it works:

Step 1: Make better use of real-time, actionable intelligence to bring the process into statistical control

Production or Quality staff weigh product samples at regular intervals and plot the data in real-time on statistical process control charts. This information gives operators and supervisors immediate statistically-based feedback when processes shift or become unstable.

This technique works for both underfill and overfill. If a process change is detected, the statistical alarms will sound and give operators the information they need to act promptly and return the process to its controlled state.

This means that operators can take immediate corrective action long before packages are underfilled or overfilled. It brings the process into statistical control so that you can take the second step in confidence.

In step 1 we collect real-time data and make sure the process is stable and predictable. The Mean (M) must be above Label Claim (Label), and no individual value (represented by the Green area) may be below the MAV. Everything above the Mean and in the yellow area is giveaway.

Step 2: Tighten the process through continuous improvement

Making better use of real-time actionable information can have a profound impact on both risk management and material use. What’s more, the information that your team has collected for monitoring the fill operation in real-time is a valuable corporate asset and has value long after the current batch of product is sealed and out the door.

Here is how it works: while weight data is collected for trend and real-time analysis, we can tag the data with relevant descriptive information. For example, we might collect information about the product type, material supplier, ambient temperatures or humidity, shift, and operator. You may remember that our window cleaner packager was tracking filler head.

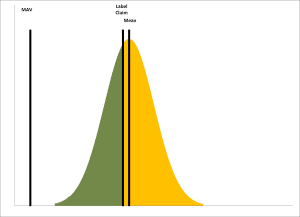

In step 2, we review the data and address underlying causes of variation.

The result is a tighter process.

This descriptive information helps us to better understand the Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How of the actual weight measurements. Wherever possible, we minimize the cost of this tag information by integration with other business systems, bar codes, RFID, and so forth.

Once we have acquired this rich matrix of information, we can slice and dice it using GainSeeker’s automated Variation Wizard. This wizard points your staff to relationships of the inputs (the context) and the outputs (the weight). Using these tools, your team should be able to begin eliminating sources of underlying variation. This pulls the tails of the distribution towards the center and increases the height of the curve.

Step 3: Shift the process

By this point you’ve learned a lot about your process. You know it is stable and predictable, and you’ve identified and eliminated the underlying causes of variation wherever possible. Now you can shift the mean of the process closer to the label weight.

You can do so with confidence because you have knowledge to support your decisions. You’ll know you can meet your label claim and minimize overpack and product giveaway.

In step 3, we shift the process closer to Label Claim.

Predicting impact

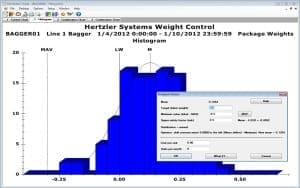

The GainSeeker Suite Platform provides another tool for this effort. The Overpack Wizard provides an easy way to predict the financial impact of reducing variation and shifting the process mean.

You can take the raw weight measurements from a given process, plug in relevant cost and production volume information, and then get a prediction of the cost impact of reducing variation and shifting the mean of the process.

The GainSeeker Overpack Wizard makes it easy to perform ‘What-if’ Analysis on your weight data.

Not just a packer’s dilemma

One other factor that needs to be mentioned: the Packer’s Dilemma isn’t just for the packaging industry. I’ve seen the same factors in play in a wide variety of industries, wherever a minimum amount of material is necessary (either for performance or for regulation) and there is not a practical limit to the amount of material that may be applied.

For example, plastics blow molding and rotational molding both require a minimum thickness of material for the product to function. However, if too much material is used, the product walls are just a little thicker. The extra material used increases the product weight and is given away to the customer.

The same principle applies in four-color production printing. I’ve been told that yellow ink is especially susceptible to overuse because over some thickness threshold it doesn’t impact the quality of the image, but it does drive up the cost, and that threshold is difficult to detect by eye.

What about you? Does the Packer’s Dilemma impact your business? What systems do you have in place to minimize the downside of the problem?

Leave a comment, below, or request a free consultation with our staff to discuss your situation, and learn how GainSeeker Suite can empower you to turn manufacturing data into real-time actionable intelligence.

[1] In 2000, Heinz settled a lawsuit regarding underfilled ketchup containers. You can read some of these stories at http://articles.latimes.com/2000/nov/30/business/fi-59336 and http://www.just-food.com/news/red-faces-for-heinz-as-ketchup-bottles-found-underfilled_id91201.aspx.

This incident came up in a discussion forum in March 2015, as published at http://science.slashdot.org/story/15/03/25/180212/scientists-create-permanently-slick-surface-so-ketchup-wont-stay-in-bottle

(These web sites accessed on April 14, 2015.)

[2] http://www.nist.gov/pml/wmd/pubs/hb133.cfm (Accessed on April 21, 2015.)